| St John's School I

was at St John's School from the age of four or five to

when I left aged fourteen in 1941 or 42. I don't remember

much about the infants except that it used to puzzle me

why one of the teachers of a class I was in used to write

the number thirty-four on the blackboard. Thirty-four was

the number of our house in Brighton Road and I couldn't

figure out why she didn't write someone else's house

number. With hindsight I now realise that she was

probably writing the date each day, thirty-four being the

year part of it.

There used to be a

big theatre in Redhill in the Central Hall. I was about

five or six when I was one of the four and twenty

blackbirds baked in a pie. I had a blackbird hood with a

big yellow beak that didn't fit me. My Mum didn't sew so

Mrs Wicks who lived two doors away altered it for me. It

must have been a school production. You go up the stairs

and into the theatre and I remember looking up and there

was this great big balcony full of people. That was an

experience.

St John's was a

church school and we used to say the catechism - the

creed. In church we used to do a lot of hymn singing and

if you got into the choir there was a bit of money to be

made singing at weddings and suchlike. Ron Moon was one

boy who I remember being in the choir. He was a good

singer. Two other boys I remember were Stan Voller and

Tony Norwood; they used to come first and second at

school every year. I was always about the middle. Stan

Voller was the same age as me, we were born on the same

day, and our paths crossed quite a few times although he

was never a particular friend of mine. Apart from being

at St John's together he joined the same army cadets as

me, so for three years we were in the army cadets

together. Then when I volunteered for the army at

seventeen and a half and went to Mark Eaton Park in

Derbyshire for training the first person I saw was Stan

Voller. I couldn't believe it. Then he married a girl

whose sister lived next door but one from us, so I'd see

he quite often when they visited her and we'd reminisce

about school and life in general.

When I went to the

big boys our first teacher there was Miss White. On of

the first things she told us was that we had left the

infants' and were now in the senior part of the school

and were there to behave ourselves. Clearly she was a

person who brooked no nonsense. She was a lovely teacher.

She said that there was something else she had to tell us

that would last us the rest of our lives and was going to

be magic. We were all ears, wondering what this magic

thing was. Eventually she told us "This is what it

is," and held up a finger. "This finger is the

magic" she continued, "for that is the distance

you leave between each word when writing." While

being perhaps a little disappointed with the 'magic'

content of the statement we were nevertheless duly

impressed. She was a lovely teacher. We used to have our

bottles of milk and if there was any over she would

distribute it among the boys who seemed the weakest. I

was small of stature and so benefited from this concern

of hers.

Other teachers were

Georgie Barnett, whose favourite saying was 'G-r-a-s-s is

Grass (as pronounced in the North), not Grarss (as

pronounced in the south), and you don't say a silly arss,

you say a silly ass.' Needless to say he was a north

country man. He was a good teacher, especially with

arithmetic. Then there was Mr Jones, a smart man about

five foot nine tall.

Mr Mole was another

teacher. He brought a real sense of comedy to school life

- he made us laugh a lot. One of the events he would

organise took place outside the school wall where the

boys' shelter now is. He got all the big boys on one side

and all the smaller boys on the other. The big boys were

the horses and the smaller boys the jockeys. Each small

boy mounted one of the 'horses', Mr Mole blew his whistle

and shouted "Start" and the object was for each

'jockey' to get the other jockeys off. No-one was allowed

to touch the 'horses' - they had enough trouble carrying

the jockeys - it was wonderful fun.

Another thing Mr

Mole organised was dry land swimming lessons. We had to

take our chairs into the playground, lay on them face

down, and he would say, "Arms out - hold it - now to

your chest ." This was practice for swimming before

we got to the pool. To go swimming we walked from the

school down the Brighton Road (passing my house on the

way) to the swimming baths in London Road, opposite the

Colman Institute. Because of the practice we'd had in the

playground - 'one. two, in, out' - half the boys could

swim as soon as they got in the water. For those who

still couldn't there'd be a couple of instructors at the

shallow end holding a piece of rope that would be tied

round you and they'd pull you along as you did the

strokes in the water. Everyone was swimming. You got a

certificate for swimming the width and another

certificate for swimming the length. That was Mr Mole, a

very good teacher. He used to walk all the way to the

baths with us. I've heard about the holes in the wall

outside the swimming baths made by boys turning pennies

into the soft brick but don't remember that we did that.

If you had a penny you'd put in in the Nestles machine

and get a small bar of chocolate. I mentioned that we

passed my house on the way down, well on the way back my

Mum would come out and give me a couple of cheese

sandwiches.

The walking we used

to do when we were at school was unbelievable. On a

swimming day I'd walk from my house to school, then to

swimming and back. Then I'd walk home to dinner and back

afterwards. Then home again at the end of school. There

were a couple of boys who didn't go home to dinner

because they lived too far away; they'd bring sandwiches.

When reading with

Mr Mole we weren't allowed to look up, we had to keep our

heads down and concentrate. If we came across a word we

didn't understand we had to raise out hand but still look

down. He'd then call out 'Yes, Holloway?' and then you

were allowed to look up and ask the question about the

word. Once the answer had been given it was heads down

again.

Other times he'd

give us a word and tell us to try to find out what we

could about it. I remember there was one word

'Vladivostok'. We'd never heard of it but it turned out

to be a seaport in Russia. Another one was Popocatépetl,

which was a volcano in Mexico. I can't remember all the

others but it was an interesting exercise.

Another teacher was

Mr Tarr. he was very good at giving lectures about the

fruit that came from South America - very interesting -

but we always seemed to finish up talking about his car,

and sometimes in his back garden in Meadvale mending it.

Mr Bradford, the

music teacher, was another good man. He used to have a

tuning fork that he hit to get us to recognise a note.

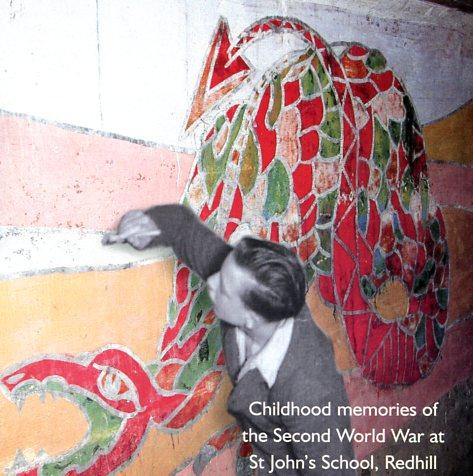

Mr Allen came very

late, when I was about twelve. I think he took a liking

to me. I liked painting and he encouraged me to keep it

up. It's still a hobby now; I've got some pictures at

home that I've painted. There were some paintings of

Robin Hood outside the classroom. Mr Allen was the arts

master whose idea it was to cover the walls of the boys'

air raid shelter in murals and I was involved in some of

the painting before I left. It was in my last year at St

John's when the Evening Standard newspaper sent a

photographer to take some pictures of the murals. We were

told in advance that they were coming and told not to

muck about but to make a good job of painting when they

were there. 'Don't overload your brush' we were told.

It's little things like that you remember. I was featured

painting the dragon in one of the photos and I remember

the photographer asking me to hold the brush in my right

hand instead of the way I naturally held it in my left,

but I never saw the resulting photo.

It seems likely

that the murals weren't painted during air raid alerts as

there would have been too many of us in the shelter.

Although I can't remember for certain it seems more

likely that they were painted when the shelters were not

in use by anyone except the class doing an art lesson. I

would say that Mr Allen probably picked about ten boys to

do the painting, although I can't quite remember. I

didn't see all the murals finished because I left before

many of them were painted. I know that Mr Allen did a lot

of the outlines of Robin Hood and other figures. There

were some pictures of Robin Hood outside ourclassroom. He

did all the skilled work, all we had to do was fill in

the colours and not go over the lines he'd drawn.

|

|

Me painting the

dragon in 1941

|

After the war the

shelter was closed and the murals forgotten. They have

since been rediscovered and are regarded with pride by St

John's School and a DVD of the school at war has been

produced. When my daughter brought me a copy of the DVD I

couldn't believe it, on its cover is a photo of a boy

painting the dragon mural. I strongly believe that this

is that Evening Standard photo and I am the boy featured

in it. I have written to the St John's headteacher and

will be going to see the murals again after seventy years

in September 2010, something I'm really looking forward

to.

I was so thrilled

to see the picture that many other memories came flooding

back too, like when I played football for the school. We

got to the final of the inter-schools competition one

year. I was left half or left wing as I had a good left

foot, and we played a team that beat us about four of

five nil. The team came from the Redhill Technical

College and they were boys who left at sixteen. We all

left at fourteen so they were all older than us, so

that's why we lost. We thought it was very unfair. My Mum

came to watch - she'd never watched me play football

before. The parents were all allowed in the grandstand

and there were quite a lot there. I was thrilled to be

playing on the sports ground pitch.

The school sports

used to be held on the Ring. I remember that Peter

Wakeman was outstanding at the high jump and Freddie

Hills was the best sprinter.

We used to have our

sports day at the Ring on Earlswood Common. There were

all the usual events and being small and light I was

quite good at long jump. They had all the prizes out

ready for the long jump winners. The first prize was a

cricket bat and I thought I'd really like that. For a

time I was winning but a boy called Ernie Taylor came and

jumped further than me and I got the second prize, a

book. I even remember its title, it was called 'Ghosts of

the Spanish Main.' It wasn't really interested in it, I'd

wanted the cricket bat. During the war the Ring was

ploughed and turned into allotments.

Then there was the

marathon every year. It started by the monument on the

top common. We called it the marathon and to us it was

quite long, about four miles.

We also used to

walk down to St John's parochial hall at the top of the

Brighton Road for sports during the war when the evacuees

were using our classrooms. I used to love that. Somebody

would bend over and you had to do a diving forward roll

over him onto one of those thick mats used in gyms. Then

the one who was worst at it would have to also bend down

so you were diving over two. Then there would be three

and if you touched someone you had to drop out. This was

all Mr Mole's competitive sports. You could finish up

with four or five to dive over. It was wonderful fun.

Another place we

used to go was Fairlawn, the big house the other side of

the laundry from the school. We were allocated a big shed

to keep our forks and spades etc. and we would do

gardening, growing vegetables.

One less than good

day at St John's that I remember vividly was when I was

about ten. I was walking to school from Redhill when I

met a boy the same age as me, John --------, who lived in

the Redstone Hollow area, and we met at the end of

Woodlands Road and walked on to school together. As we

got to the school there was a big milk lorry at the

bottom of the slope going up to the infants. John bent

down, picked up a matchstick and started letting the air

out of one of the tyres. Alarmed I said to John,

"What are you doing?" He brushed it off as

nothing. Now coming down the hill on his bike at that

moment was Mr Mole. He said, "I'll see you two boys

later." When we got to school we were reported to

the headmaster, Mr Bennett. John went first and Mr

Bennett said that Mr Mole had seen him letting the air

out of the tyre and asked him what he had to say for

himself. He said "I'm sorry, Sir." Mr Bennett

replied, "Well, you're having three of the best; do

you want the thick cane or the thin cane?" We heard

that the thick one didn't hurt as much. John had three on

each hand and came out crying. I went in and Mr Bennett

said, "What have you got to say, Holloway?" I

said, "I didn't know what he was going to do. I did

ask him what he thought he was up to. I didn't know he

was going to pick up a match and . . . . " I was

trying to defend myself; I was ten, and at that age you

can't put words together properly. He said, "You're

as bad as him - three on each hand." And that's what

I got. I really didn't deserve that and was disappointed

that justice as meted out by Mr Bennett could be so

unfair. I was a little kid, scrawny, weak, no dad - it

was the only time I ever had the cane and I've never

forgotten that day. When I got home I told my Mum and she

said that it had happened and I'd have to put up with it.

If you're in pain that's not want you want to hear. I had

welts come up on on my hands and I couldn't write for a

while after. I loved St John's but that was one day I

didn't love. If I'd been guilty I might have accepted the

punishment but I wasn't guilty and didn't deserve it, and

as you can tell I'm still indignant to this day. About

four years ago (2006) I was at South Park Con Club

playing snooker when four blokes walked in. They were

golfers and because it was raining hard they couldn't

play golf and came for a game of snooker instead. One

kept looking at me and came over. He said, "Charlie

Holloway?" "Who are you?" I asked.

"John Ashby." I hadn't seen him since the St

John's days. I said "John, you got me the bloody

cane!"

|